(Continued from Part 2/3)

Similar to the fact that Ireland has a binary system of higher education, the business sector in the country is also divided into two, with one being foreign-owned and the other being indigenous.

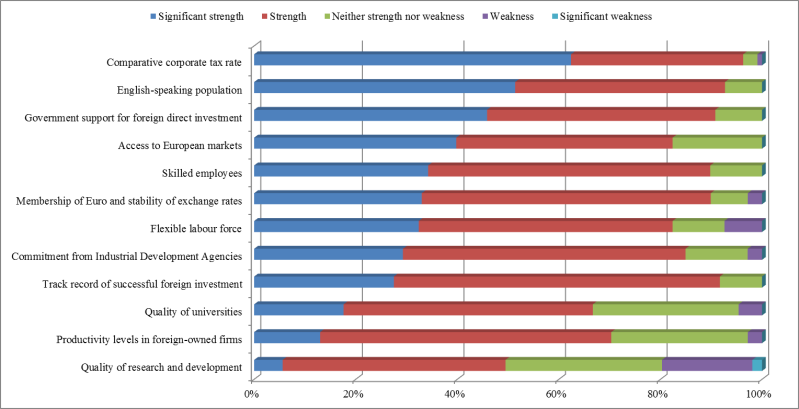

The historical success of Ireland in attracting a substantial amount of FDIs has led to an industrial base strongly dependent on multinationals and oversea exports. It is not difficult for one to find that a relatively small number of foreign-owned companies are responsible for the majority of Business Expenditure on Research & Development (BERD) in Ireland, an indication to show not only the strong performance of multinational firms but also the ‘unsatisfactory’ performance of the so-called indigenous firms.

More interestingly, it seems that foreign-owned firms and indigenous firms are concentrated in distinct sectors; for example, high-tech sectors like ICT and pharmaceutical are obviously dominated by multinationals.

A comparison of the amount of expenditure on R&D by sector reveals that the higher education sector, which is, in this regard, largely dominated by the seven universities plus the Dublin Institute of Technology, outperforms the indigenous business sector and the government (and public) sector.

The strengths of Irish universities have further been intensified after nearly a decade of state support in the area of research and development. Admittedly, the Irish government has also called for, and indeed made some efforts in supporting the growth of indigenous small to medium-sized firms, this sort of investment is not comparable to what universities have been receiving.

It is based on these facts that we argue that it is time Irish universities build closer relationships with foreign-owned companies during a period when previous advantages of the country are in the risk of weakening. In particular, we would like to introduce an embeddedness approach which is adapted from the ‘Triple Helix’ model popularised by Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff in 1997.

Figure 1 A ‘Node-Channel’ model of G-U-I interactions in Ireland (Foreign-own firms on the left; Indigenous firms on the right)

Figure 1 above shows a ‘Node-Channel’ model of interactions of three main regional stakeholders in Ireland – government, university, industry – in which node stands for strength of each sector and channel refers to linkages between each other. Following the categorisation of many previous studies, in this figure we divide the industry node into two smaller nodes (foreign-owned firms and indigenous firms). In relative terms, we consider that Ireland has R&D strength in the university sector and foreign-owned firms, less so in domestic firms and the government sector, however there is plenty of room for improvements in inter-firm linkages and university-industry collaborations.